No state has a more intimate relationship with avocados and the trees on which they grow than California.

Avocados are not only the California’s official state fruit; they are an integral component of the local culture and economy. Aside from the fruits, which provide an obvious (and delicious) appeal, the lush foliage of avocado trees can lend a tropical feel to your yard or garden.

While they are poorly suited for the chilly climate characteristic of the northern half of the state, avocado trees grow well in southern California, where their popularity continues to climb.

Origin and History

Avocado trees (Persea americana) were originally native to the lush forests of Mexico and portions of Central America. However, fossil evidence suggests that avocado trees (or some of their closest relatives) may have ranged farther north than current wild avocados do, potentially including parts of southern California.

Because avocados are too large to be wholly consumed by any extant animal that shares their natural range, scientists suspect that they co-evolved with now extinct animals, such as giant ground sloths. Only such massive animals could engulf the fruits, swallow the seeds and expel them unharmed, which would allow the seeds to grow into new avocado trees (check out this PBS video that further explores the topic of fruits and their extinct predators).

However, before the plants could disappear into the annals of history, humans began consuming the fruits. While the seeds are obviously much too large for humans to ingest, these new bipedal predators took over the role of seed disperser for the trees. Many seeds were scattered inadvertently as humans fed on the fruit, but eventually, humans would begin planting the seeds deliberately.

Avocados played an important role in the cultural lives of both the Aztecs and the ancient Mayans. In fact, the Mayans believed that important people could be “reborn” through the trees. Accordingly, Mayans often planted numerous avocado trees around their homes and in places of spiritual significance.

Mayans first began consuming avocados nearly 10,000 years ago, and they domesticated the fruit-bearing trees about 5,000 years ago. By contrast, Europeans didn’t become familiar with the fruit until Spanish explorers encountered them in the early 16th century.

After European discovery, avocados slowly made their way around the globe. Although they remained an expensive delicacy, avocados started becoming commercially important by the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They remained relatively expensive until the beginning of the 21st century, when relaxed trade agreements allowed millions of Mexican avocados to begin entering the United States.

Avocado Tree Basics

Avocado trees are dense evergreens, which can reach heights of up to 60 feet or more. However, most cultivated specimens remain in the 10- to 30-foot range (depending on the variety chosen). Some growers prune their trees to keep them relatively short and facilitate easier harvest, but this is not strictly necessary.

Avocado trees usually grow in a punctuated fashion, in which they produce an abundance of new shoots and leaves during a short period of time. Trees living in warm locations tend to do so several times over the course of a single season, while those growing in cooler climates usually only experience one such growth period per year. In general, avocado trees grow relatively quickly, occasionally adding as much as 24 inches of height each year.

However, despite their rapid growth rate, avocado trees mature slowly. Most will not produce flowers and set fruit until they reach at least 5 years of age, and some require nearly three times this much time to mature. Even then, the vast majority of the tree’s flowers will fail to become fruit – statistically, about 1 in 10,000 avocado tree flowers become fruit.

Though they are evergreen, avocado trees often replace a large number of their leaves each spring. The discarded leaves help to produce a rich leaf litter underneath the tree, which may provide some health benefits and deter the growth of weeds, as well as various bacterial and fungal rots.

Because avocados are understory trees (and are therefore not often subjected to high winds), they typically produce very shallow root systems. These roots are not very effective at drawing water from the ground, and they hardly ever penetrate far enough to access deep-water reserves, so they typically require supplemental water when planted outside their native range.

The Unique Flowers of Avocado Trees

Avocado trees are monoecious (in the broad sense of the term) and have very unusual flowers. Although the flowers are considered “perfect,” and feature both male and female structures, the flowers alternate between operating as males and operating as females. They function as females upon opening, before switching to a male reproductive mode later – botanists call this sequential hermaphroditism dichogamy.

Avocado trees flower in one of two patterns, termed “Type A” and “Type B.” Type A flowers open as females on the first morning, before starting to operate as males on the second afternoon. Type B flowers function as females on the first afternoon they open, before switching to a male reproductive mode on their second morning. Both types of flowers close permanently at the conclusion of their second day.

While avocado trees have a limited ability to self-pollinate, many growers improve the pollination rate by planting rows of Type A trees beside Type B trees.

The Avocado Fruit

Botanically speaking, avocados are large, single-seeded berries. Avocados are a slowly maturing fruit; most spend at least 6 to 12 months on the tree before harvest, and some remain on the tree for as long as 18 months. Avocados do not ripen on the tree – they must be removed and stored for about two weeks. After this time, they will become soft and delicious.

The average tree produces about 150 fruit each year, but exceptional specimens can produce more than 500 avocados in a season. This is a substantial quantity of fruit for a tree to support; 500 avocados weigh about 200 pounds.

Occasionally, avocados fail to reach large size or produce a seed. Such fruits are referred to as “cukes,” because of their superficial resemblance to cucumbers. While many farmers simply discard these deformed fruits (which occur due to incomplete pollination), others market and sell them.

Growing Your Own Avocado Trees

While most avocados are produced via grafting, homeowners and amateur gardeners often grow avocados from seed.

To germinate a seed, suspend it with toothpicks over a glass of water so that about 1 inch of the seed is immersed. The seed should sprout in about 3 to 6 weeks (occasionally sooner). Once the stem has reached a height of about 6 to 8 inches, cut it in half to let the roots develop more fully. Once the roots have thickened and leaves have begun reappearing on the plant, move the seed to a small pot filled with rich soil. Keep about half of the seed above the level of the soil.

While you can germinate seeds at any time of the year, spring is the best season to plant avocados outdoors. Whether you are transferring a seed you germinated yourself or a container-grown plant purchased at a nursery, you must be sure to plant the tree well when moving it outdoors.

You must choose your planting location carefully when setting out to plant your avocado tree. Try to plant your new tree so that it receives as much sun exposure as possible, but be mindful of sun scorch in delicate young plants. Additionally, mature avocado root systems can be problematic, as they may lift sidewalks and other hardscapes, so think carefully about the place in which you want to plant your new tree. Avocado trees absolutely require well-aerated soils, and compacted substrates spell their doom. Avocado trees rarely thrive when planted in lawns, so try to install them away from such places.

Prepare a planting hole with twice the diameter of the root ball, but only make the hole as deep as the root ball is tall. Because of their shallow-rooting habit, staking the newly planted tree is often wise.

Young avocado plants need copious amounts of water, but the substrate must never become saturated. Water first year plants two to three times per week, but reduce the supplemental water schedule to once per week after the tree has reached one year of age.

Threats to Avocado Trees

Avocado trees can fall victim to a variety insect pests, as well as several bacterial and fungal pathogens.

Some of the most common insect pests of avocado trees include western avocado leafrollers (Amorbia cuneana), avocado brown mites (Oligonychus punicae), avocado thrips (Scirtothrips perseae) and persea mites (Oligonychusperseae). More generalized insects, such as grasshoppers, and other invertebrates, such as garden snails also plague young trees.

Most of these pests can be at least partially controlled with the use of predatory insects, but proper maintenance practices also help farmers keep losses to a minimum. Additionally, it is advantageous to encourage the presence of natural predators, such as spiders, frogs, lizards and birds, as their feeding activities will help keep the avocado pest population in check.

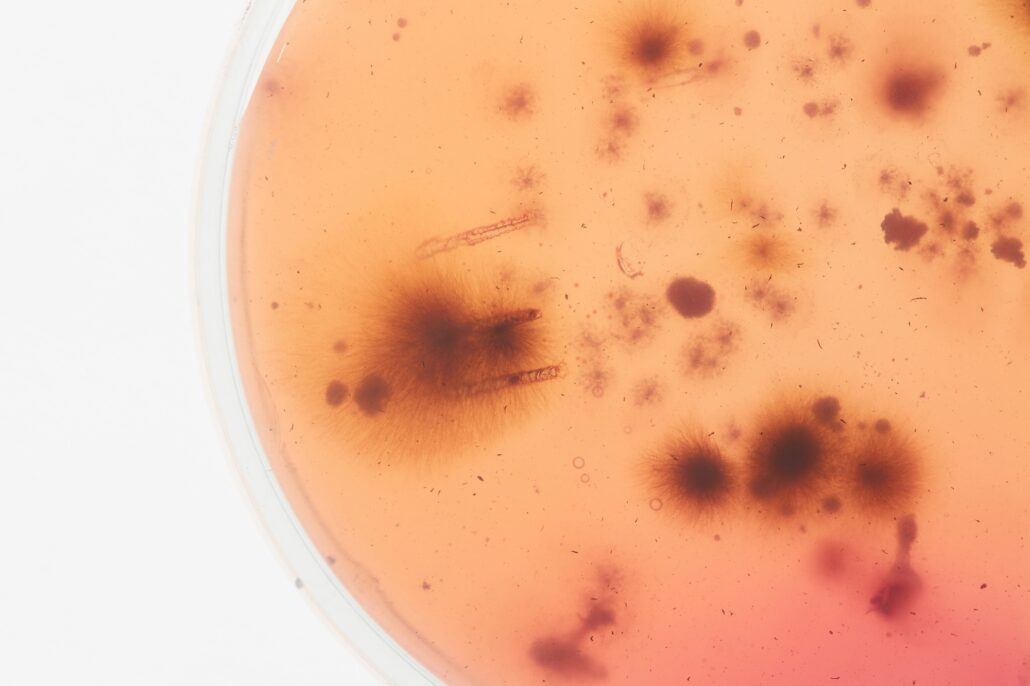

Several common, opportunistic pathogens – including oak root fungus (Armillaria mellea) and anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) – can afflict avocado trees. Additionally, several pathogens that preferentially attack avocado trees, such as Avocado root rot (Phytophthora cinnamomi), are also common problems for avocado growers. Proper irrigation and planting help prevent these problems, as does the use of resistant rootstocks. Canopy dieback and yellowing foliage are two of the most obvious signs of root rot.

One particularly perplexing disease of avocado trees is called avocado black streak. Although scientists do not yet understand what organism causes this condition, whose most obvious symptom includes the development of large cankers, it appears most common in stressed trees. Accordingly, the best way for avoiding this potentially fatal affliction is to provide the trees with the highest quality care possible – especially as it relates to irrigation.

Avocado Classification and Varieties

Although they evolved in tropical latitudes, avocado trees have historically grown in several different habitats. This led to the development of three separate, but closely related, races: Mexican, Guatemalan and West Indian. Most botanists recognize these distinct races as members of the same species, but sometimes, these three races are elevated to the level of formal subspecies or varieties. In such cases, the three forms are referred to as drymifolia, guatamalensis and americana, respectively.

Fortunately for the modern avocado industry, some of these forms grow quite well in Mediterranean climates, which has led to their popularity among California’s agricultural industry. Over time, growers have combined the three races in various ways, to produce hundreds of different avocado varieties.

Seven different avocado varieties are produced commercially in California, including the Hass, Zutano, Reed, Pinkerton, Lamb Hass, Gwen, Fuerte and Bacon varieties. Despite this diverse array of choices to the state’s farmers, the overwhelming majority of avocados produced in California are of the Hass variety.

The Hass variety is popular for a variety of reasons. Unlike most of the others, Hass avocados change color (from deep green to purple-black) when they ripen, which allows consumers to purchase the fruit confidently. Hass avocados also have a wonderful taste and a skin resilient enough to resist the indignities of nationwide shipping, storage and stocking. They also have a very long shelf life, relative to other varieties.

The different varieties not only produce fruit with different qualities, but also the trees tend to exhibit different growth habits. The Hass variety, for example, grows into an umbrella-shaped tree, while the Reed variety tends to take on a columnar growth habit. The varieties also differ in terms of size, which can be an especially important consideration for homeowners with limited space.

Market and Demand

In the last ten years, avocados have become one of America’s favorite fruits. Americans consume almost 2 billion pounds of the high-fat fruit each year, and Los Angeles area shoppers are responsible for devouring about 300 million individual fruit each year – tops in the country (San Francisco and San Diego are also ranked among the top 10 cities for avocado consumption).

Of course, it makes perfect sense that southern California is the epicenter of avocado demand – 9 out of 10 avocados produced in the U.S. come from within the state’s borders. Half of these are produced in San Diego County. However, the majority of avocados consumed in the U.S. continue to be imported from Mexico, the world’s leading producer of the fruit.

The world’s second leading producer of the fruit is Chile, but they only produce about one-quarter of the total produced by Mexico. Other important avocado-producing countries include the Dominican Republic, Indonesia, Columbia, Peru and the United States.

The recent drought was difficult for most California farmers, including those growing avocado trees. However, farmers and researchers from the University of California have recently experimented with different maintenance techniques to help alleviate some of the pressures on avocado farmers.

Specifically, they made two changes: Farmers began pruning their trees shorter than they had in the past, and they started planting trees twice as close to each other as they had been. Whereas conventional wisdom recommended planting avocado trees 20 feet away from each other, farmers began planting them only 10 feet apart. This allowed the farmers to lower their water usage slightly, while drastically increasing their yield.